Design And Analysis Of Lean Production Systems .Pdf Download UPDATED

Design And Analysis Of Lean Production Systems .Pdf Download

From Lean Production to Lean 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review with a Historical Perspective

1

LEANBOX SL, Distrito [e-mail protected] C/Juan de Austria 126, 08018 Barcelona, Spain

2

I3A—Universidad de Zaragoza, C/María de Luna, 3, 50018 Zaragoza, Spain

3

ESEIAAT—Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, C/Colom, 11, 08222 Barcelona, Espana

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Academic Editor: Maurizio Faccio

Received: half-dozen October 2021 / Revised: 28 October 2021 / Accepted: 29 October 2021 / Published: 3 Nov 2021

Abstract

Over recent decades, the increasing competitiveness of markets has propagated the term "lean" to depict the direction concept for improving productivity, quality, and lead time in industrial as well as services operations. Its overuse and linkage to different specifiers (surnames) have created confusion and misunderstanding equally the term approximates businesslike ambivalence. Through a systematic literature review, this study takes a historical perspective to analyze 4962 papers and 20 seminal books in order to clarify the origin, development, and diversification of the lean concept. Our master contribution lies in identifying 17 specifiers for the term "lean" and proposing four mechanisms to explain this diversification. Our research results are useful to both academics and practitioners to return to the Lean origins in order to create new research areas and comport organizational transformations based on solid concepts. We conclude that the use of "lean" as a systemic thinking is likely to be further extended to new enquiry fields.

ane. Introduction

Over recent decades, markets accept go more than and more than competitive equally they progressively demand customized products and services at lower prices and with shorter delivery times [i]. In the operations field, lean has become a widespread direction organization that is suitable for achieving these competitiveness targets [two,3,4] through more efficient processes, shorter lead times, and greater flexibility in supplying a wide variety of products and services in small quantities [five].

As a result, the management concept of lean has spread profusely throughout industry and services over the terminal xl years [3]. A huge amount of research is now available for scholars and practitioners, with the nowadays work having identified 4962 academic papers with "lean" in the championship and "lean manufacturing" generating viii,910,000 results through a Google search.

When a term becomes popular and stylish, its overuse runs the risk of devaluing its original meaning and may create inconsistencies and ambiguities [6,7]. In addition, the term "lean" leads to more semantic confusion because it is frequently joined with specifiers by way of "surnames" related to a wide variety of fields and uses.

In practice, the term "lean" approximates businesslike ambiguity, as described by Giroux [viii] and similarly assessed in terms of the lean culture concept by Dorval et al. [ix]. What is even worse, equally Schonberger recently warns [7], information technology may be in adventure of disintegration.

Indeed, this misunderstanding is 1 of the bug that lean practitioners confront when implementing an organizational change and they need to align lexicon and terminology with common conceptions [4].

The objective of this written report is to provide a historical perspective on the lean concept past clarifying its origins, evolution, and how it became diversified from its original concept up until today. Furthermore, this research aims to help scholars, practitioners, and managers seeking to render to the lean origins in order to better sympathise the evolution and electric current land of this field of knowledge.

From a methodological point of view, this enquiry has followed the principles of the systematic literature review (SLR). Templier and Paré [ten] have classified literature reviews into iv types: narrative (summarizes previous published inquiry); developmental (provides new conceptualizations or methodological approaches); cumulative (compiles empirical prove and draws conclusions about a topic of interest); and aggregative (tests specific research hypotheses or propositions, with iii subtypes: systematic, meta-assay and umbrella review). The historical arroyo of this research falls under both cumulative and aggregative literature reviews.

Tranfield et al. [11] propose methodologically adapting SLR from medical science to management science, while Denver and Transfield [12] developed their method even further. SLR has been used in previous studies on lean topics [three,4,ix,xiii,fourteen,fifteen]. This study follows the SLR methodology as defined past Denver and Tranfield [12], and it uses the PRISMA 2020 checklist [xvi] to ensure that a rigorous SLR process has been used.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted an SLR in accord with the five steps proposed by Denyer et al. [12]: question formulation; locating studies; study selection and evaluation; analysis; synthesis; reporting; and using results.

two.one. Question Conception

Equally introduced above, this study aims to answer the following research questions:

-

RQ1: What is the historical origin of the term "lean"?

-

RQ2: What are the previously used terms (if any) for the lean concept?

-

RQ3: How has the term "lean" evolved over fourth dimension?

2.ii. Locating Studies

Three bibliographical materials take been used:LISTORDE

-

English linguistic communication records at the Web of Science database from 1950 to 2020.

-

English language records at the Scopus database from 1987 to 2020.

-

Books: We analyzed a collection of 20 seminal hardcopy books published between 1977 and 2020.

ii.2.ane. Locating Database Records

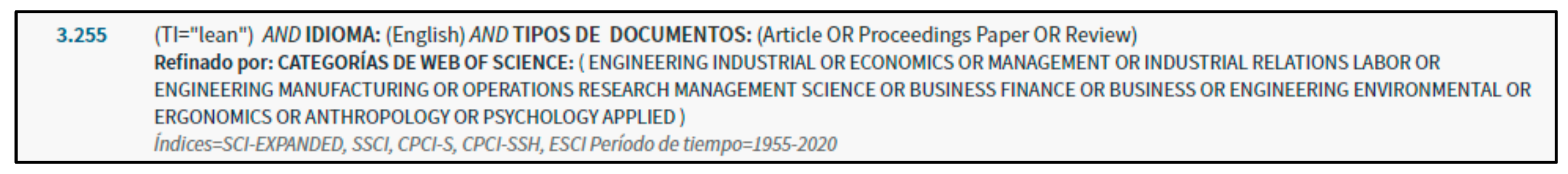

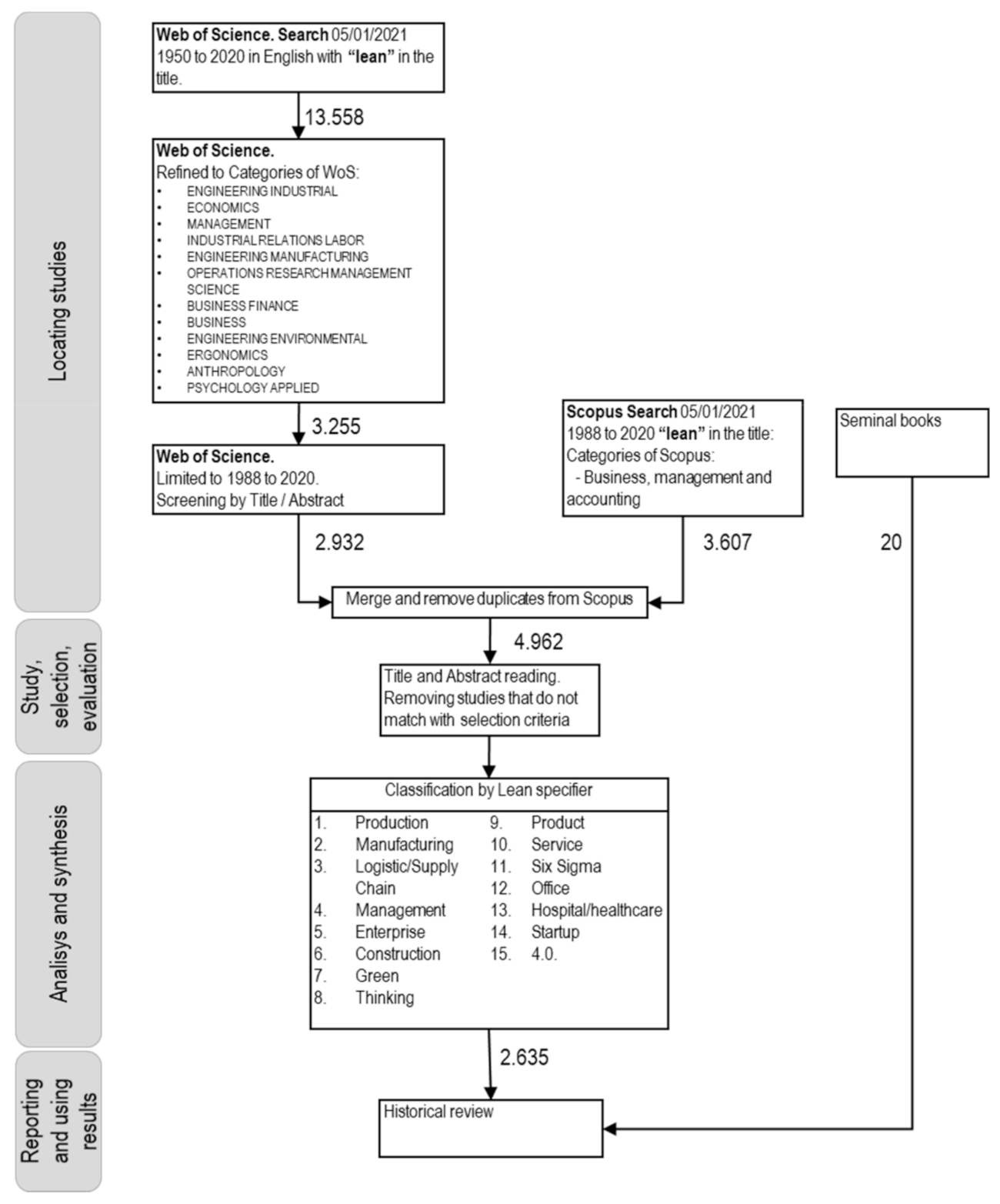

As proposed past Sinha et al. [17] (p. 304), we searched for the keyword "lean" in titles to ensure our focus on both the historical involvement and evolution of the topic. A first search on Spider web of Scientific discipline conducted on 5 January 2021 provided 13,558 records containing the word "lean" in the title. An initial quick review showed that "lean" is a pop term in other disciplines too. Therefore, our search was refined to some related WoS categories. The concluding search string is shown in Effigy i.

This second bounded search on 5 January 2021 provided a total of 3255 records, which nosotros transferred to a spreadsheet for analysis and classification.

In a showtime assay, the most cited studies were analyzed [one,5,6,8,18,xix] to uncover any general understanding on the origins of the term "lean" in the field of management, by which we constitute it was outset coined in 1988.

Even though records from 1950 to 1988 were reviewed, simply one similar and metaphorical use of "lean" was institute [20]: "Managerial Productivity: Who Is Fat and What Is Lean?". Withal, this case in management research was not fully associated with its later use in operations management where information technology was fully developed.

We performed a manual review based on the WoS category and title analysis in order to remove whatever records of non-related topics (e.g., combustion, food, data, chemicals, etc.). Works published ahead of print (early access) were discarded. Finally, 2932 records were retained for farther analysis.

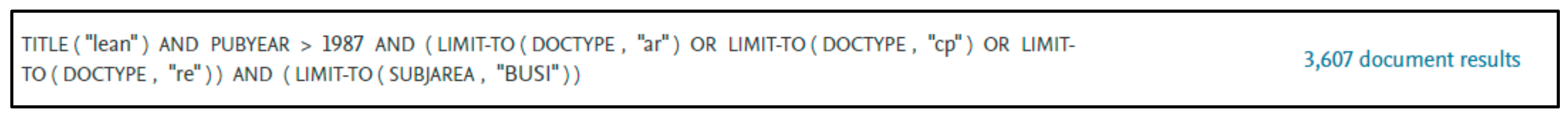

Similarly, a Scopus database search was made on the same date (5 Jan 2021) for studies published in the English language later 1987, restricting these to items labelled as articles, conference papers, and reviews. These were farther limited to the subject field areas of concern, management, and accounting. The Scopus search cord is shown in Effigy 2.

The records were transferred to a spreadsheet, merged with those from the WoS search, and redundancies were removed. Finally, a total of 4962 records were kept for further analysis.

A showtime transmission review based on reading the titles and, if necessary, the abstruse allowed us to determine the selection criteria for the records, every bit described in Section 2.3.

The SLR process is shown in Figure iii.

2.2.two. Books

Books were nerveless based on the Holweg's list [19] (p. 434), new titles were added to this listing. A total of 20 seminal hardcopy books were analyzed. Books were gathered from private collections or were caused at https://www.bookfinder.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2021).

2.iii. Study Selection and Evaluation

To select the relevant records associated with the research questions, their titles and abstracts were analyzed. The following selection criteria were defined:

-

The championship allows confirming that the term "lean" is used as a managerial concept.

-

The abstract confirms that the term "lean" is related to operations management.

To avoid bias, if neither title nor abstract immune classifying the tape, information technology was removed.

2.4. Analysis and Synthesis

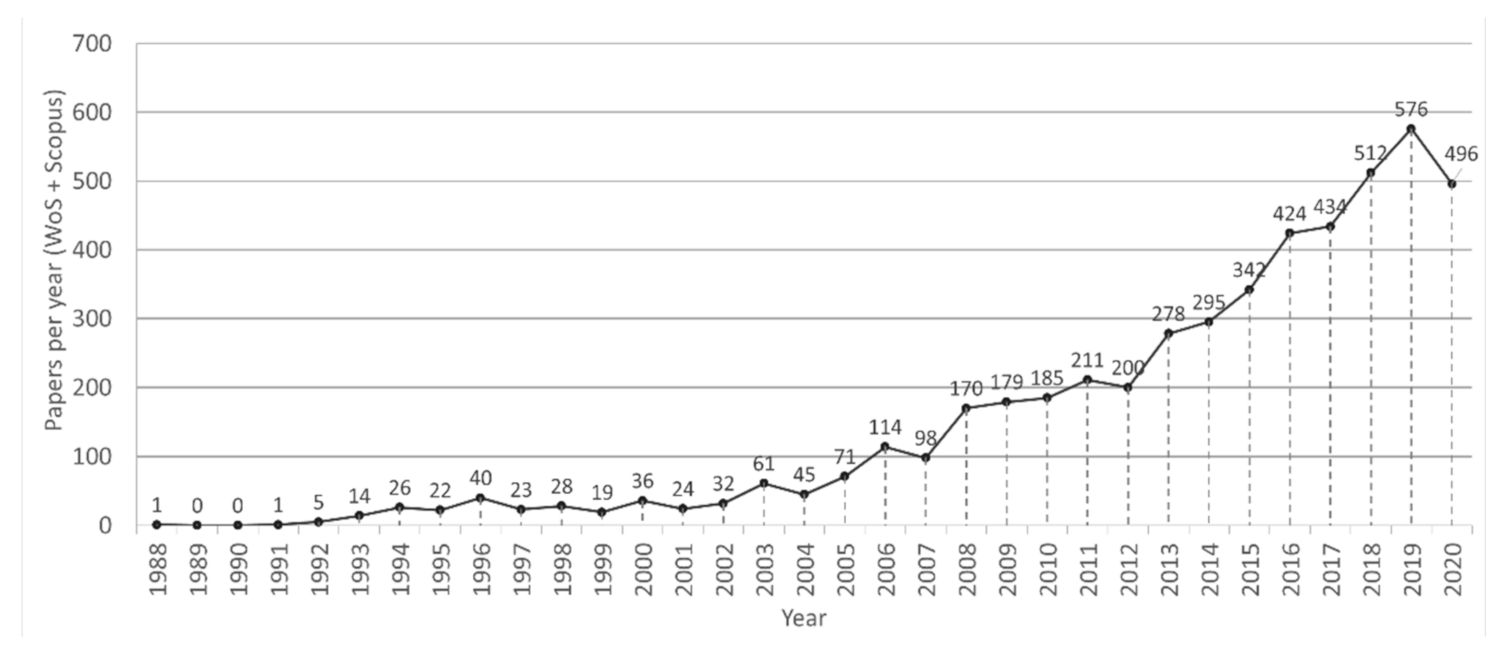

After choice was washed, the database records were analyzed based on the bibliometric measure "papers-per-twelvemonth" (Figure 4).

During our analysis of the titles, the primary lean specifiers ("surnames") were found and we appropriately classified the records under the post-obit categories (by chronological order of appearance): production, manufacturing, logistics/supply chain, direction, enterprise, construction, green, thinking, product, service, 6 sigma, office, healthcare/infirmary, start up, 4.0.

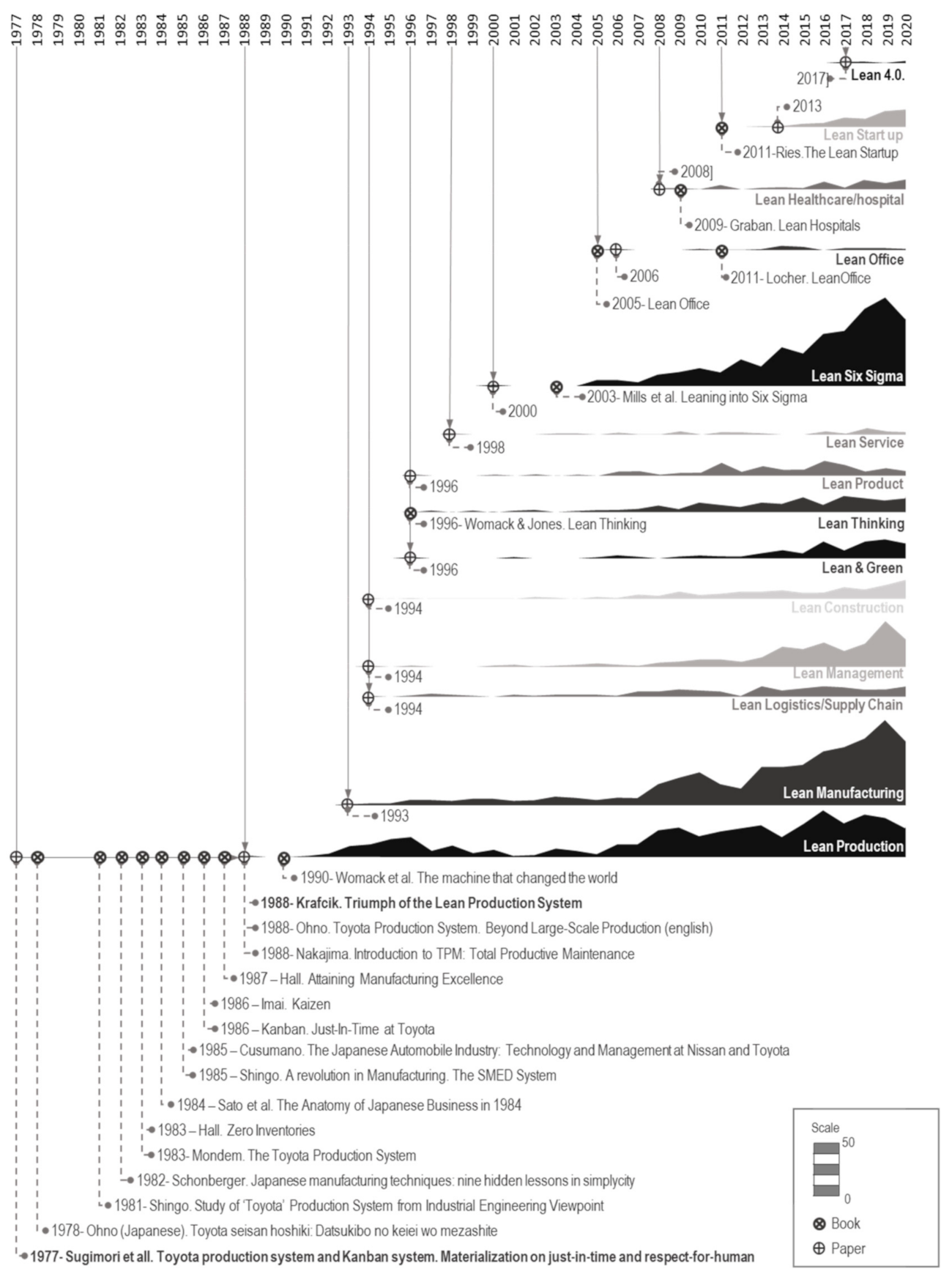

To facilitate the historical analysis, nosotros created a full general nautical chart split into categories (Effigy 5): the nearly relevant categories are represented by a line starting at the year of their foundational paper or book; the line thickness is proportional to the paper-per-year bibliometric (run across calibration in the same Figure 5).

3. Results

3.1. Origin and Previously Used Terms for the Lean Concept in Operations Direction

In answering RQ1 (What is the historical origin of the term "lean"?), we found a general consensus [one,2,half-dozen,thirteen,19,21,22] that the term "lean" was coined in the International Motor Vehicle Program (IMVP) and published for the first time in 1998 by John F. Krafcik, in the academic paper titled Triumph of the Lean Product Organisation, when he stated "lean typology builds on the piece of work of International Motor Vehicle Program researchers Haruo Shimada and John Paul Max Duffie, who utilise the terms 'robust' and 'delicate' to denote similar concepts" [23] (p. 51). Here, Krafcik is referring to the 1986 working paper Industrial Relations and "Humanware" [24].

The word "lean" was chosen for its more positive sense [xix] (p. 426) or, as suggested by New, "as an adequate mode of describing Toyota production organisation without offending the other sponsors of the IMVP" [22] (p. 3547).

Therefore, to answer RQ2 (What are the previously used terms (if whatever) for the lean concept?), nosotros must return to the foundations of the Toyota Production System. There is wide agreement [5,vi,9,22] that the first English language paper introducing the term "Toyota production organisation" (TPS) was presented in Tokyo past Sugimori et al. in 1977 [25]: Toyota Production Organisation and Kanban System. Materialization of But-in-Fourth dimension and Respect-for-Human Arrangement. This seminal paper based TPS on two pillars: just-in-time and respect-for-humans. The authors acknowledged Taiichi Ohno as having been the promoter and leader of TPS since at least 1957.

Ohno's seminal 1978 book (published only in Japanese) was Toyota seisan hoshiki: Datsukibo no keiei wo mezashite [26], and his first paper translated to English dates dorsum to 1982 [27] (How the Toyota Production Organization Was Created, republished in The Anatomy of Japanese Business in 1984 [28]). This early translation offered an alternative and more than accurate translation to simply-in-time: "right on time" which was not adopted.

The first book in the English language describing TPS was published in 1981 by Shigeo Shingo: Study of "TOYOTA", Production System from Industrial Engineering Viewpoint [29]. He acknowledged Ohno equally the promoter of TPS (pp. 19–32) and postulated that his own book would provide a more than applied caption. It was a highly influential book in which Shingo insisted repeatedly on an essential systemic view in order to understand TPS. This book was republished with a better English translation in 1989 past Productivity Press [29].

In 1983, Yasuhiro Monden published Toyota Product System: Practical Arroyo to Production Direction [30]. The foreword by Ohno highlighted the fantabulous conceptualization of the TPS. Without losing the holistic vision, tools and methodologies were profusely described.

The first Western researchers interested in the topic were very influenced by these early on books, and they published their works in the period between 1983 and 1988, during which different "nicknames" were used to refer to the TPS:

-

Japanese Manufacturing Techniques, by Schonberger (1982) is the beginning book written in English and it described "stockless production" and "JIT Production" [31] (p. 17).

-

Hall, in his volume Goose egg Inventory (1983) [32] (p. one) adopted the term "stockless production". In another volume, Attaining Manufacturing Excellence (1987) [33] (p. 23), he summarized the virtually used terms at the time: "manufacturing excellence", "value-added manufacturing", "continuous comeback manufacturing", and "JIT/TQ".

-

Cusumano's book The Japanese Automobile Industry (1985) [34] (pp. 262–307) described the foundations and development of TPS with a historical perspective, although he did non propose any culling terms.

-

In the context of IMTV, "fragile production" was already being used in 1986 [24].

From 1985 to 1990, different TPS tools were documented in item, thus providing progressively greater understanding but fragmenting the overall vision past "using the part for the whole", as Shah [6] (p. 786) suggested. Some examples of these TPS tools are: SMED (1985) [35], Kanban (1986) [36], Kaizen (1986) [37], and TPM (1988) [38].

In 1988, the English language translation [39] of Ohno's [26] book was published: Toyota Product System: Across Large-Calibration Production.

To summarize the answer to RQ2, the lean product system can be considered a way of naming the Toyota production organisation without naming Toyota. With the same intention, other terms were proposed prior to 1988 by taking some of the more relevant parts of the organisation as inspiration: Japanese manufacturing techniques, stockless production, JIT production, value-added product, continuous improvement manufacturing, not-stock production, delicate production.

3.2. Answering RQ3. Historical Development of the Term "Lean"

As already pointed out, the expression "lean production arrangement" was coined by Krafcik in 1988 [23]. The seminal and best-selling volume, The Machine that Changed the World [21], popularized the term "lean production"; and earlier similar expressions were completely abandoned (with the only exception being only-in-time, which survived in the supply chain literature until now).

Womack et al. [21] used the term "lean product" in contrast to "mass product" with the intentions of setting a criterion, although the original systemic vision was lost. This is probably the starting time symptom of the "lack of stardom between the systems and its components" as Sha et al. [6] suggested.

Thus, 1990 can exist considered the year when the term "lean" became popularized as an operations management concept. From 1990 to 1995, the term "lean" was adopted in the literature mainly equally "lean production". The first research papers focused on either supporting or questioning lean [forty,41,42] while describing the first lean experiences and the limits of this do [42].

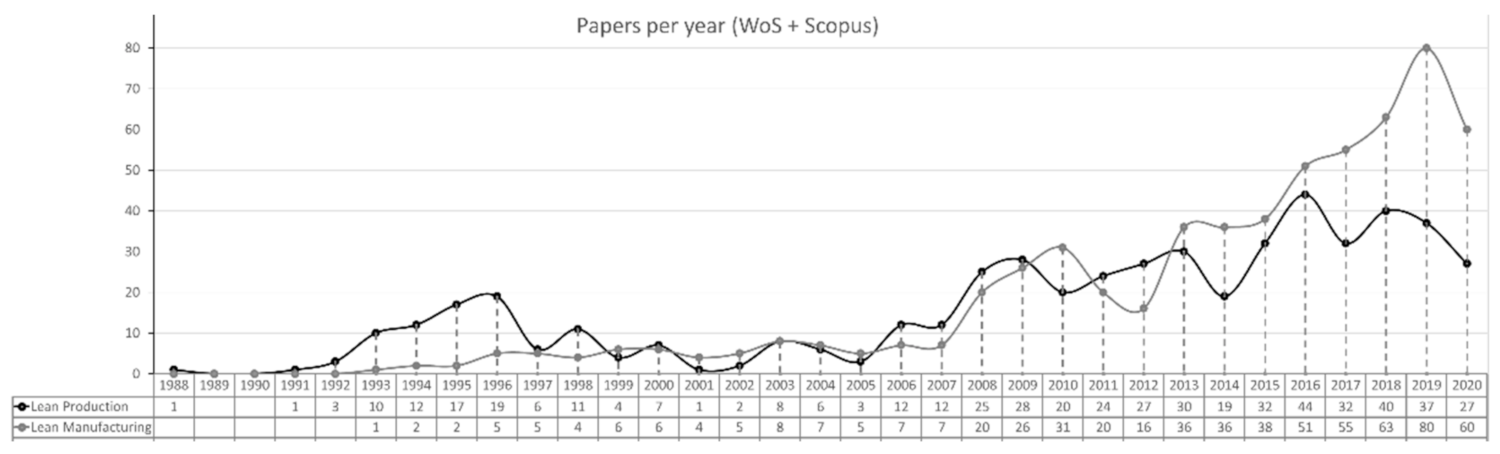

In 1991, Delbridge et al. [43] introduced "lean manufacturing" as a synonym for "lean production", and this term became more popular afterwards 2000. Present, "lean manufacturing" is the preferred expression for referring to lean in industrial operations (Figure 5).

From 1992 to 1996, some authors intended to upgrade lean to a more conceptual level by introducing the terms "lean management", "lean enterprise" [44], and "lean thinking" [45]. This opened the door to using the term in non-manufacturing contexts, such equally the services sector.

In parallel, the menstruum 1994 to 2000 saw the beginning attempts to apply lean to dissimilar production contexts (lean construction) also as to others outside pure product (lean logistics, lean supply chain) or by combining it with supplementary topics (lean and green, lean product, lean 6 sigma). The fragmentation of the lean arrangement into its tools continued with books such as Lean Toolbox [46]

It was not until 2005 that the lean concept opened its scope to the services sector, mainly under the umbrella of lean six sigma, lean function, lean healthcare/hospital, and, recently, lean startup.

Finally, in 2017, lean 4.0 appeared as a promising style for new developments by fusing lean and Manufacture 4.0 technologies.

All in all, the term "lean", which was initially conceptualized as a "lean production organization", has evolved from 1988 to 2020 as a "living concept". This evolution can be ascribed to the post-obit proposed mechanisms that mostly combined with each other over time:

-

Expansion: extending the concept in the operations field.

-

Transfer: applying the concept across production.

-

Targeting: focusing the concept on a particular sector.

-

Combination: merging the concept with other concepts.

Through analyses of the scientific literature, this work has identified the most of import lean specifiers ("surnames"). They are presented in chronological society of their advent and describe (a) the first record found in our database analyses; (b) the historical trajectory based on the most relevant publications; (c) the development mechanisms; and (d) the present situation in terms of research interests. A chart with the yearly evolution of papers-per-year complements the summary.

three.ii.one. Lean Production (1988)

Introduced in 1988 by Krafcik every bit the "lean product organisation" [23], this expression was used as an alternative to the "Toyota production system". Information technology was fully adopted after publication of the seminal book The Machine that Inverse the World [21], which described lean production (LP) as an alternative to mass production [2], whereby the original holistic approach of TPS was partially lost.

Interest in LP grew betwixt 1992 and 1996 (encounter Effigy 6), then diminished from 1997 to 2007. Since 2008, it has once over again go of academic interest, along with lean manufacturing.

In 2007, Holweg [19] outlined a detailed historical evolution of the term, which was highly influenced past MIT research. The same year, Sha et al. [6] analyzed the historical context and reported for the offset fourth dimension the semantic confusion surrounding the term "lean product" while also reinforcing the conception of lean "equally a system", for which he identified x dimensions useful to researchers.

In 2013, Marodin et al. [47] identified half-dozen research areas in the field and provided another alarm about the system conception becoming fragmented and dissociated. In 2015, Jasti et al. [1] concluded that LP continues to take a high impact on academia, practitioners, and consultants. They further propose a holistic rather than "bits-and-pieces" approach [1] (p. 16).

In 2015, The Analysis of Manufacture 4.0 and Lean Product [48] presented the first comparative study betwixt LP and I4.0. With 17 papers published in the last v years, the interrelationship betwixt LP and I4.0 has clearly awakened new involvement in this research field [49,50].

3.2.2. Lean Manufacturing (1993)

In 1993, Powell introduced lean manufacturing (LM) in a like sense to lean production: Lean Manufacturing Organization, 21st Century [51].

In 2003, [52], Shah et al. likewise used this term with the same meaning every bit lean product and focused the topic on manufacturing plant direction. In 2013, Bhamu et al. [5] presented the development of LM definitions.

The most recent main reviews of lean manufacturing that confirm this equivalence with lean production were published between 2019 and 2020 [3,four,five,53]. These reviews are perhaps targeted more to the fields of industry and, specifically, factory management.

In 2016 [54], the beginning linkage with Industry 4.0 was made. Until 2020, the relationships between LM and Industry 4.0 were explored. In the concluding one, published in 2020 [55], Valamede et al. offered a holistic view toward integrating both concepts.

Equally a conclusion, lean manufacturing tin can be considered synonymous with lean production, although targeted more at mill operations. Afterwards 2000, is the preferred term in the bookish literature when referring to lean in the industrial field (Figure 6). That is probably to distinguish the product of appurtenances, since the term "product" is used more and more in the service industries.

3.ii.3. Lean Logistics (1994), Lean Supply (1996) and Lean Supply Chain (1999)

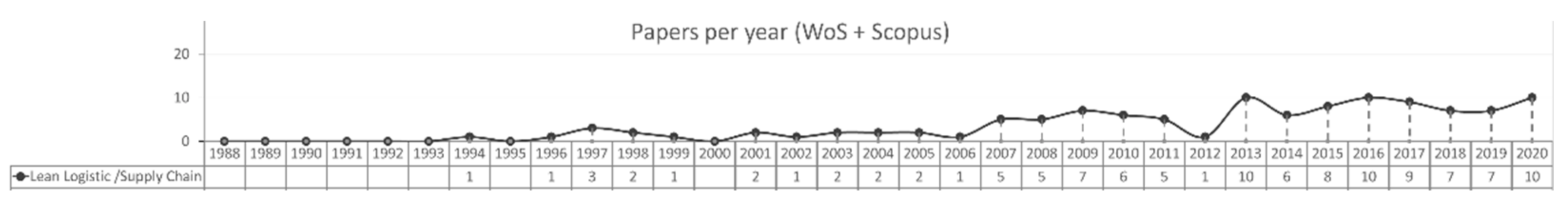

The first paper on lean logistics (LL) was authored by Fynes et al. in 1994, From Lean Production to Lean Logistics: The Case of Microsoft Ireland [56], which illustrated the expansion from product to supply chain management.

In 1996, the first paper to use using "lean supply" was Squaring Lean Supply with Supply Concatenation Direction [57], in which the authors extended the concept to supply chain management.

In 1999, the first paper to apply "lean supply chain" (LSC) was Vertical Integration in a Lean Supply Chain: Brazilian Auto Component Parts [58], which related the term "lean" to a broader perspective on supply concatenation management.

The three surnames can exist considered quite equivalent, in that they focus on: the efficiency of material flows inside and outside the manufactory; the integration and evolution of suppliers; and the integration of different actors and information across the supply chain [59].

García Buendía et al. (2020) [60] presented a conceptual development map of the concepts behind lean supply chain direction over the last 22 years.

Relationships between lean supply concatenation and I4.0 have appeared in recent years in publications on different topics, such as the impact of these on performance improvement [61,62,63,64] and their further relationships with information and digital technologies [63].

To conclude, these specifiers appeared equally lean expanded to supply chain management: "Lean logistics […] is based around extended TPS right along supply concatenation from customers right dorsum to raw material extraction" [64] (p. 171).

The iii surnames in this field extend lean perspective to supply chain management, with interest having increased moderately since 2007 (Figure 7).

3.2.4. Lean Management (1994)

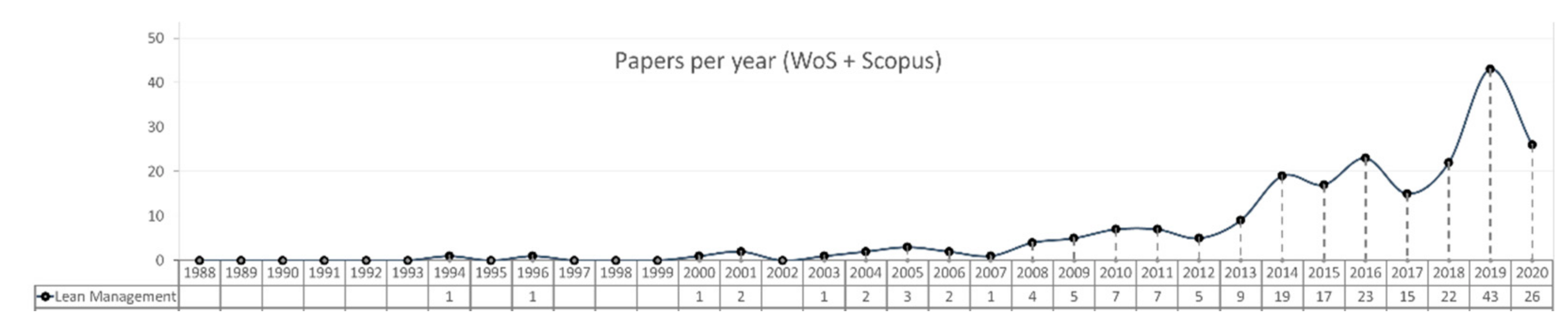

The origins of the term "lean management" (LMg) are unclear. The first reference in the English language bookish literature was introduced by Petrovic et al. in 1994: Business Process Re-Engineering every bit an Enabling Factor for Lean Direction [65]. Even so, the German literature has used this term since 1992. It seems to be a starting time endeavor at shifting towards a more than managerial concept in a similar mode as the later emergence of lean enterprise or lean thinking.

In whatever instance, information technology was non until 2008 that the literature showed consistent interest in the topic.

In 2014, Martinez-Jurado et al. [66] presented the term in association with organizational sustainability. More recently in 2019, Sinha et al. [17] considered lean management to be an extension "into an inter-disciplinary subject with linkages to operations management, organizational behaviour, and strategic direction".

In 2016, the start paper on LMg and I4.0 was published: Industry four.0. The End Lean Direction? [67], concluding at the fourth dimension that the correlations between both concepts were depression.

Equally a decision, lean management tin be considered equally a transfer to a more than managerial approach. Information technology refers to adopting lean principles in order to manage an entire organization. Although quite neglected until 2008, it has generated growing interest in the past decade, at least, up until 2019 (Figure 8).

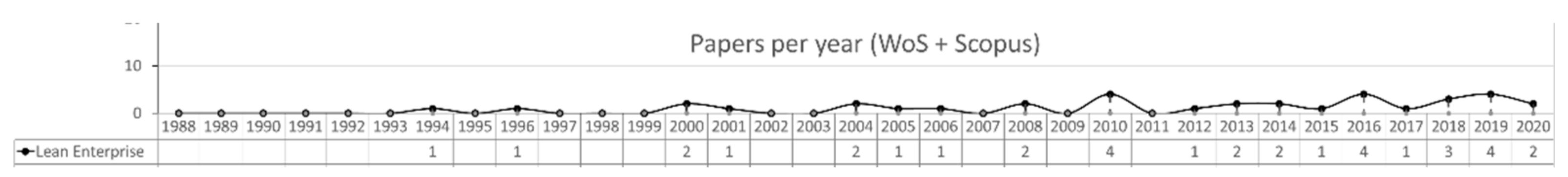

3.2.v. Lean Entreprise (1994)

The expression "lean enterprise" (LE) was coined in 1994 by Womack and Jones in their volume From Lean Production to the Lean Enterprise [44], in which lean shifts toward a more abstract concept: "the lean enterprise is a group of individuals, functions, and legally separate but operationally synchronized companies that creates, sells, and services a family of product".

As a conclusion, lean enterprise can be considered a transfer to a more abstract concept. The term has not been widely adopted in literature, just it remains live, equally evidenced in the last review published in 2020 [68] and the first proposals linking LE with 4.0 technologies [69] (Figure nine).

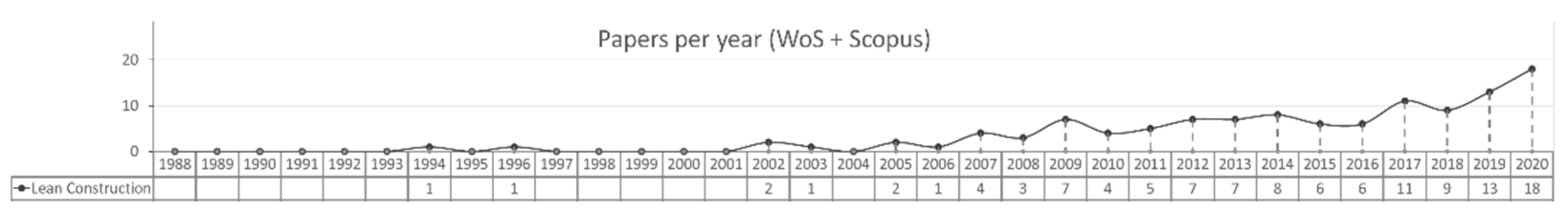

3.ii.half-dozen. Lean Construction (1994)

The first indexed reference to lean structure (LC) dates back to 1994, when Koskela published the proceedings paper Lean Construction [lxx], which placed lean product in the detail context of a product (a building) that cannot be moved in a continuous flow.

It was not until 2002 when research attention returned to the topic [71], and in 2006 Salem et al. [72] proposed a practical view toward implementing lean tools.

In 2019, Koskela presented an epistemological perspective non only on LC only also on lean and its Japanese origins [73]. In 2020, Lekan et al. [74] proposed "Construction 4.0" as the link between LC and "Industry 4.0" with the aim to go farther in construction operations efficiency.

The terminal review [75] was published in 2020, and it explored the barriers to implementing LC.

As a conclusion, lean construction targeted this specific sector in which the product cannot be moved in a continuous flow. It adapts lean principles and tools to this item production process. It was quite ignored until 2008, but the topic has generated moderately increasing interest in the past decade, recently linked with I4.0 (Effigy 10).

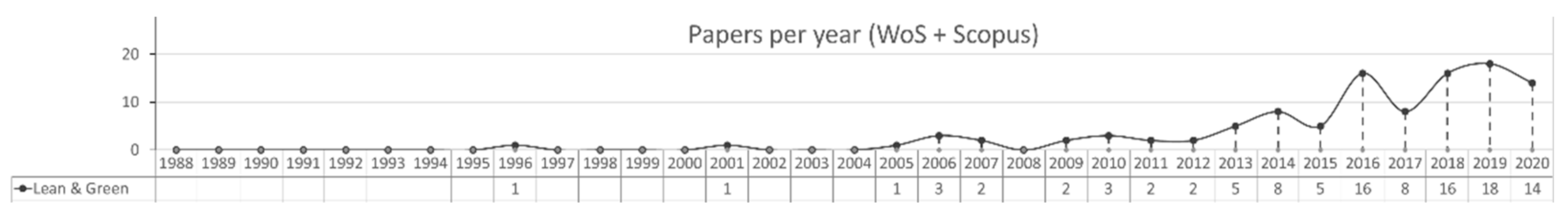

3.2.7. Lean and Green (1996)

Lean and green (L&Grand) appeared in a 1996 Florida publication [76]: Lean and Green: The Motion to Environmentally Witting Manufacturing. It integrates process improvements with reductions in environmental impact.

The first publications on 50&G focused on how to constitute a link between lean principles and environmental practices, with an emphasis mainly on manufacturing [77] and supply chain management [78].

Interest in the topic has increased since 2013, and the offset literature review (in 2015) [79] proposed it as a specialized research area. In 2019, Farias et al. developed a systemic approach [lxxx,81].

Recently the scope has been extended to products and services [82], likewise as combined with Industry 4.0 bug [83,84]

As a determination, lean and green (sometimes green lean) emerged as a combination with environmental and sustainability concepts. It refers to the synergy between lean and environmental preservation. More specifically, it focuses on how lean practices tin can contribute to reducing environmental impact while maintaining profits primarily in operations, but also in services and product blueprint. The topic has generated increasing research interest since 2013 (Figure 11).

3.2.8. Lean Thinking (1996)

Lean thinking (LT) was introduced in 1996 by Womack and Jones [45] in their all-time-selling book Lean Thinking: Banish Waste material and Create Wealth in Your Corporation. With intentions similar to lean enterprise, the term can be considered a shift toward a philosophy of eliminating waste in organizations. This way of thinking is structured in v steps: specify value; identify the value stream; flow; pull; and pursue perfection.

The first indexed commodity is from 1997 [85], and it analyzes the impact of LT and LE on the marketing processes. In 2004, Hines et al. [xviii] published a very detailed report on the topic, first with its genesis and moving on to identify both the successes and difficulties of Western companies applying LT. The last review was published in 2020 [86], and information technology explored the synergies between LT and Industry four.0 while further suggesting how LT could trigger I4.0 solutions.

Equally a conclusion, lean thinking is a transfer to a more abstruse arroyo. It refers to adopting a way of thinking in order to make radical improvements in whatsoever arrangement. Research involvement in this topic has remained moderate and stable in the past decade (Effigy 12).

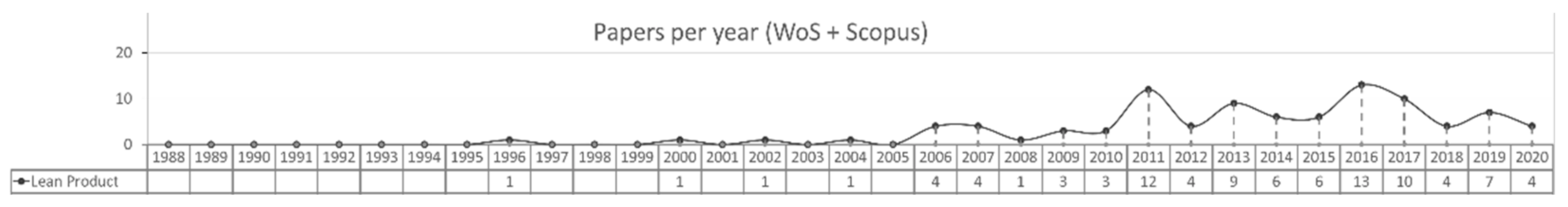

3.2.9. Lean Product (1996)

The first newspaper, The Hard Path to Lean Product Development, by Karlsson et al. [87], introduced the expression "lean product" in 1996 as an extension to production development. It refers to fast, efficient, and low-price product development [88].

The concept was created for concrete goods and generated low interest amid researchers until 2006. The same year, Liker et al. [89] proposed the concept in order to get "across manufacturing to whatsoever technical or service" with a systemic view toward "integrating people, procedure and tools".

The commencement review in 2011 [88] showed the historical links between LP and TPS while presenting a list of conceptual principles.

In 2015, Sassanelli et al. [90] introduced a systemic view that focused specially on services as a lean product service organisation. This approach was recently analyzed in the latest systematic reviews on the topic [91].

As a conclusion, lean production extends to product development in terms of both goods and services. It has generated moderate and stable interest since 2006 (Figure thirteen).

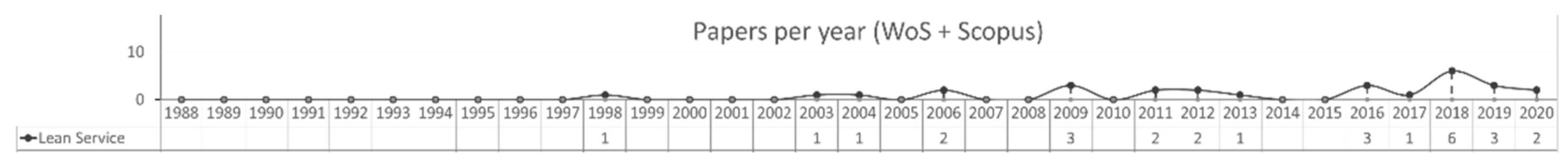

3.2.x. Lean Service (1998)

Lean service (LSe) was proposed in 1998 past Bowen et al. in their article Lean Service: In defence of a Production-line Approach [92] in society to extend lean to industrial services. The adjacent indexed paper was published in 2003: The Lean Service Automobile [93], which adapted lean production to an insurance visitor (JPF).

LSe refers to applying lean principles and tools toward the improved efficiency of non-manufacturing services [94] such as insurance firms [93], telephone call centers [95], financial services [96], banking, and healthcare services [97].

A systematic review published in 2016 [98] ended that lean was applicable in services with limitations, and it identified LSe as a nascent research surface area.

As a determination, lean services transfer from manufacturing to service processes. Information technology refers to applying lean manufacturing principles and tools that accept been adapted to services production. Researchers have shown fiddling interest in it, probably because this perspective is as well explored past lean six sigma scholars (Figure xiv).

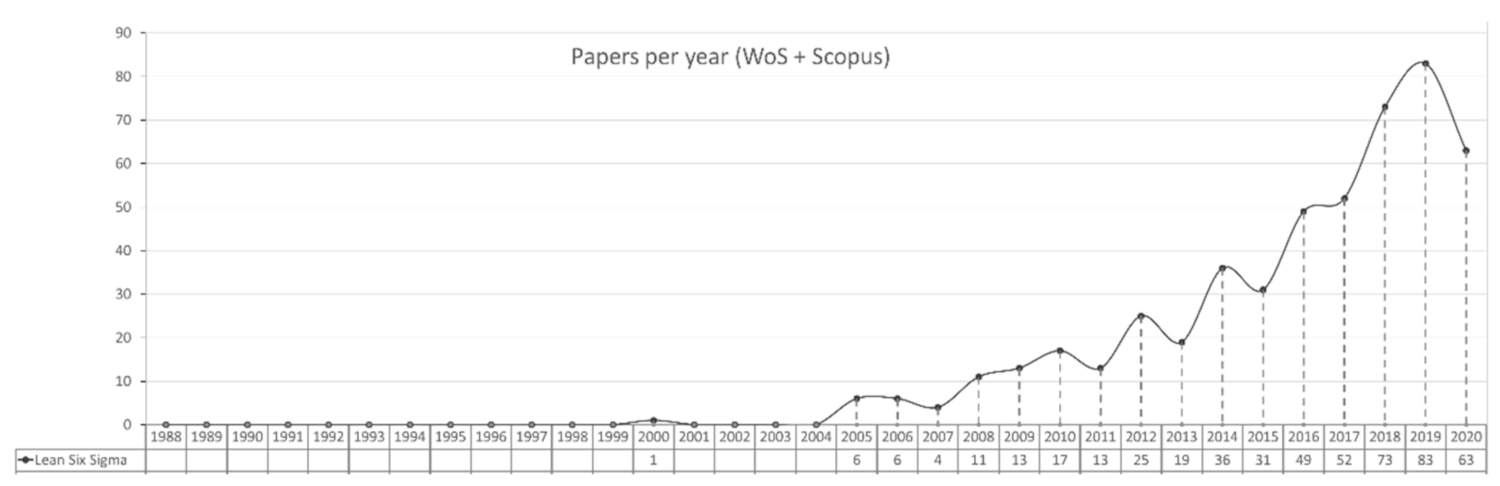

3.2.11. Lean Six Sigma and Lean Sigma (2000)

The first published reference to this field appeared in 2000 every bit "lean sigma" [99] in the article "Lean Sigma Synergy"; only information technology was non until 2005 when the first indexed newspaper used "lean six sigma" (LSS) equally "an approach focused on improving quality, reducing variation and eliminating waste product in an organization" [100].

Lean vi sigma merged lean and 6 sigma, which are 2 disciplines that, if not in opposition to each other, were at least in competition until 2003. In this year, the volume Leaning into Half-dozen Sigma [101] attempted to bring together together the all-time practices from lean and six sigma [102].

Later on 2005, the concept has generated increasing interest amongst researchers, as shown in the evolution of published papers (particularly after 2013) in contexts of both manufacturing [103] and service [104]. Recent research has shown interest in the links with Industry 4.0 [105,106].

As a conclusion, lean vi sigma and lean sigma is a combination of the principles and tools from lean manufacturing (reducing waste) and six sigma (reducing variability and promoting leadership). Originally created for manufacturing industries, it extended its implementation to services too. Interest in this topic has increased sharply between 2004 and 2019 (Figure xv).

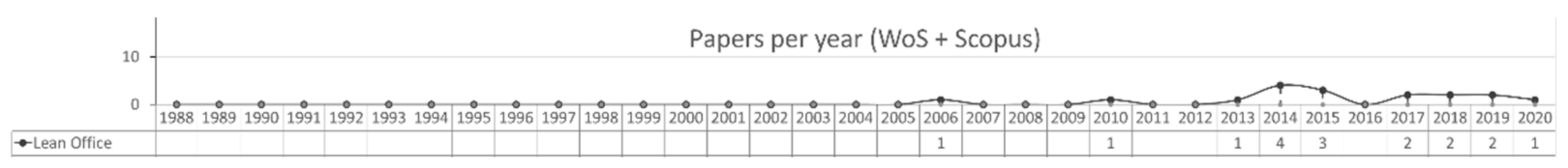

3.2.12. Lean Office (2005)

Lean office (LO) appeared in 2005 with the book The Lean Role [107], collecting applied cases from 2000 to 2004 of extending lean to not-manufacturing environments.

In 2011, Locher published Lean Office [108] with a methodological and holistic arroyo to utilize lean in services, commercial and authoritative environments.

The very limited academic literature available starts on 2006 with Herkommer et al., Lean Part-Arrangement [109] and focuses on surface optimization, workplace improvements [110], and information flows in administrative processes [111]. A systematic literature review published in 2019 [112] described implementation issues and areas of enquiry.

As a decision, lean role is a transfer to not-manufacturing environments with a focus on improving efficiency at the administrative level. The scant academic interest in this topic lies in stark contrast to the term'southward popularity amid practitioners (Figure 16)

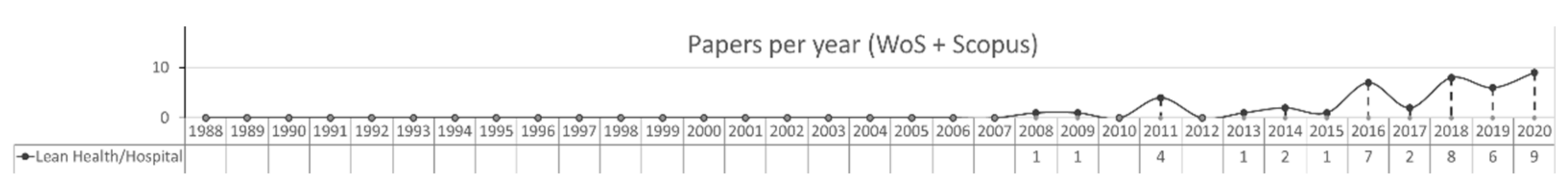

3.2.13. Lean Healthcare/Hospital (2008)

In 2008, Portioli-Staudacher used the term "lean healthcare" for the first time in the newspaper: Lean Healthcare. An experience in Italia [113] published equally a lean approach to the healthcare sector. The paper did non focus on service comeback but in how to reduce inventories of drugs and other healthcare supplies by implementing tools from lean logistics.

In 2009, Marker Graban published the volume Lean Hospitals [114] as a practical guide for adapting lean tools in hospital management.

In 2011 [115], lean healthcare was proposed as a more holistic system for improving healthcare organizations and how to assess them.

In 2016 [116], Costa et al. presented a review based on vi parameters: research method, land, healthcare area, implementation, lean tools and methods, and results.

In 2020, Santos et al. [117] highlighted new research areas for the time to come.

Every bit a conclusion, lean healthcare/infirmary is a transfer to services, targeted on healthcare services, and it includes hospital management. Information technology applies lean principles and tools toward improving patient care. Interest in it was very limited until 2015, and information technology has seen moderate growth in the last 3 years as new research proposals are put forth (Effigy 17).

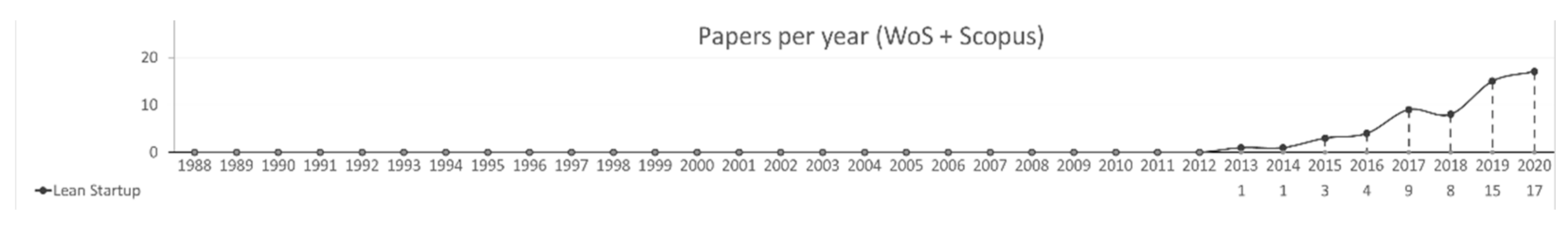

iii.two.14. Lean Startup (2011)

The first reference to the term "lean startup" in the research literature was past Blank in 2013, in Why the Lean Start-up Changes Everything [118]. The author expanded on the concept proposed past Ries in his 2011 volume The Lean Startup [119], proposing information technology as a new methodology for launching companies faster and cheaper than the methods of a traditional concern plan. Equally a effect, the term can be considered a variation that applies lean principles to the launching of new businesses.

In 2017, Frederiksen et al. [120] presented prove from the scientific literature for their in-depth look at the methodological proposals in Ries'due south volume.

In 2018, Bortolini et al. [121] clarified how the foundations of lean startup are linked with lean manufacturing: maximizing customer value while minimizing waste.

In 2020, Silva et al. [122] provided new perspectives on developing a business concern model and discussed complementary methodologies, such as active methodologies and client development.

As a conclusion, lean startup is a transfer to launching a new business concern. It uses lean principles to launch new business concern models while reducing time-to-market and minimizing initial investment and risks. Since its appearance in 2011, involvement in the topic has seen sustained growth (Effigy 18).

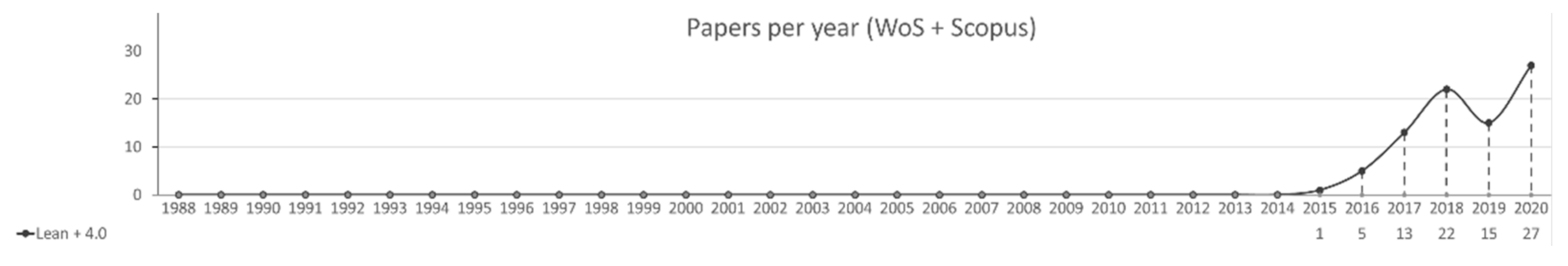

3.2.xv. Lean iv.0 (2017)

Lean four.0 (L4.0) is the most recent specifier. It was introduced in 2017 past Metternich et al. [123] in the German language paper Lean 4.0—Between Contradiction and Vision, which combined lean with Industry 4.0 (I4.0). The authors reverberate on the compatibility between lean philosophy and technologies nether the umbrella of I4.0, concluding that lean appears to be a prerequisite for digitization.

In 2018, Mayr et al. [124] agreed that lean enabled the successful introduction of I4.0 and ended that both views complement each other. They nowadays a detailed overview on how the about relevant lean tools can be complemented with I4.0 technologies.

In 2020, Valamede et al. [125] went farther by taking a holistic view to identify 25 synergy points between lean tools and 4.0 technologies. Perico et al. [126] proposed new perspectives on how to comprise artificial intelligence to support homo decisions in cardinal lean 4.0 topics (production control, maintaining continuous pull menstruation, and early prediction of car failure). Nether the denomination "lean Industry 4.0", Ejsmont et al. [127] identified the enquiry trends combining "lean management" and I4.0. to go further in reducing waste to achieve a new level of operational excellence.

At the present moment, simply iv papers take been plant with "lean 4.0" in the title, although increasing involvement (see Figure 19) is existence generated in the relationships between Industry 4.0 and unlike lean aspects: lean production [49,128], lean manufacturing [54,129], lean and light-green [85,130], lean structure [74], lean enterprise [seventy], lean healthcare [131], lean management [132], lean six sigma [133], lean supply chain [64], and lean thinking [86].

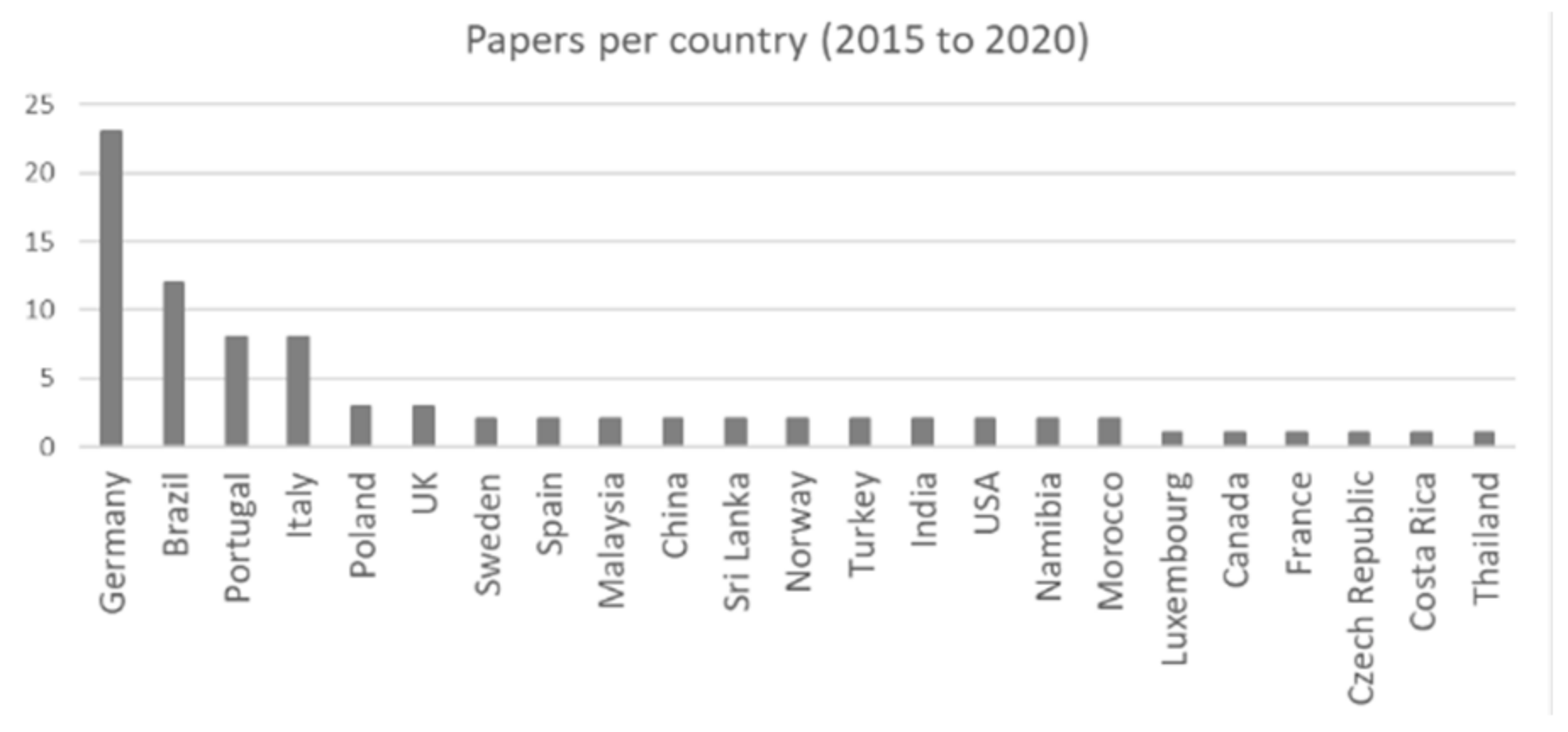

In total, 83 papers have been identified linking "lean" and I4.0. An analysis based on the address of the respective writer shows countries leading the enquiry in this topic: Frg is in the start position equally the term "Industry iv.0" was coined in Germany. Still, an arising interest is shown in different nations, particularly in Brazil, Portugal and Italy (run into Figure xx).

Equally a conclusion, lean iv.0 is a combination of lean manufacturing (or lean production) principles and tools with Manufacture four.0 technologies. It deals with the synergies and complementarity of I4.0 with lean with the intention of reducing waste material and complexity. It appears to be a promising field of research in the coming years.

four. Conclusions

This commodity explores the origins and diversification of the term "lean" equally a management concept, in both the manufacturing and service sectors. It takes a historical perspective in answering 3 research questions. To achieve this, 4.962 indexed records and twenty seminal books were analyzed by following a systematic literature review methodology.

Our research questions tin can be answered as follows:

Near the historical origin of the term "lean": it was created in 1988 as "lean product system", a generic denomination for the Toyota production organisation. The acknowledged book, The Machine that Changed the World (1990), populated the term "lean production" by absorbing other alternative expressions that existed at that time.

The previously used terms (which had similar intentions of denominating the Toyota production system without naming Toyota) were: Japanese manufacturing techniques, stockless production, JIT product, value-added production, continuous improvement manufacturing, non-stock production, and fragile production.

Since 1990, the term lean has evolved over time. Its evolution and diversification can be explained through 4 mechanisms (combined over time): expansion, transfer, targeting, and combination. This resulted in the creation of a confusing puzzle of lean specifier.

This newspaper has outlined the paths of evolution by using the most cited specifiers in the academic literature:

-

Between 1990 and 2000, the term lean remained mainly in its original field of operations management, with the following specifiers: lean production, lean manufacturing, lean logistics, lean supply chain, lean production, lean construction, and lean and light-green. The offset try to upgrade the concept to a more conceptual level was greeted with initially limited academic involvement: lean management, lean enterprise, and lean thinking.

-

In 2000, the combined term "lean half dozen sigma" emerged and up to the present has received much attention in both the manufacturing and service sectors.

-

Since 2006, the term "lean" was progressively applied in the service field with new specifiers: lean service, lean hospital, lean healthcare, lean part, lean startup.

-

The final specifier, lean 4.0., was created in 2017 equally a synergetic combination between lean manufacturing (or lean production) and the Industry 4.0 image. At the moment, it focuses simply on the manufacturing field.

The term "lean", as a management concept that allows organizations to remain competitive past removing waste from their processes, has been fully adopted by management researchers. Based on a bibliometric analysis of published papers-per-year, nosotros can say that research interest in this topic has grown exponentially since 1988.

This paper reveals some implications for future inquiry: The apply of lean perspective can be further extended beyond its current evolution, adapting its principles and tools to different sectors or applications. The diversification mechanisms described above tin can open up new enquiry areas in a fast-irresolute, complex and competitive world. The lean arroyo combined with the new emerging disruptive technologies (and then-chosen Manufacture 4.0) open new avenues for future research equally intelligent construction, sustainability, smart cities, environmental improvement or public governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G.-V.; methodology, F.G.-V. and A.S.; formal analysis, J.A.Y.-F.; investigation, F.M.-Five.; information curation, F.1000.-V.; writing—original draft grooming, F.Chiliad.-V.; writing—review and editing, A.South.; supervision, J.A.Y.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was funded by the DGA-FSE (Diputación General de Aragón—Fondo Social Europeo) project T56_20R: Grupo de Ingeniería de Fabricación y Metrología Avanzada.

Institutional Review Board Argument

Not applicative.

Informed Consent Argument

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of involvement.

References

- Jasti, North.V.M.; Kodali, R. Lean production: Literature review and trends. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 53, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano-Fuentes, J.; Sacristán-Díaz, M. Learning on lean: A review of thinking and research. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 32, 551–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, Due east.; Antony, J. Enquiry gaps in Lean manufacturing: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 815–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, J.; Psomas, E.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Hines, P. Practical implications and future research agenda of lean manufacturing: A systematic literature review. Prod. Plan. Command. 2020, 32, 889–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamu, J.; Sangwan, One thousand.S. Lean manufacturing: Literature review and inquiry bug. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 876–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Ward, P.T. Defining and developing measures of lean production. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 785–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonberger, R.J.; Schonberger, R.J. The disintegration of lean manufacturing and lean management. Omnibus. Horizons 2019, 62, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H. 'It Was Such a Handy Term': Management Fashions and Pragmatic Ambiguity. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1227–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorval, Chiliad.; Jobin, G.-H.; Benomar, N. Lean culture: A comprehensive systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2019, 68, 920–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templier, G.; Paré, G. A Framework for Guiding and Evaluating Literature Reviews. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2015, 37, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a Systematic Review. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; SAGE: Grand Oaks, CA, United states, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ciano, M.P.; Pozzi, R.; Rossi, T.; Strozzi, F. How IJPR has addressed 'lean': A literature review using bibliometric tools. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 5284–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, P.; Manfè, Five.; Romano, P. A Systematic Literature Review on Recent Lean Research: State-of-the-art and Futurity Directions. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 579–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.; Saurin, T. Lean product in complex socio-technical systems: A systematic literature review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 45, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, East.A.; Brennan, S.East.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 argument: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, N.; Matharu, M. A comprehensive insight into Lean management: Literature review and trends. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2019, 12, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, P.; Holweg, M.; Rich, N. Learning to evolve. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2004, 24, 994–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holweg, G. The genealogy of lean production. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 25, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayles, L.R. Managerial Productivity: Who Is Fatty and What Is Lean? Interfaces 1985, 15, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havn, E.; Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T.; Ross, D. The Machine that Changed the World; Rawson Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- New, Due south.J. Celebrating the enigma: The continuing puzzle of the Toyota Production Arrangement. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 3545–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafcik, J.F. Triumph of the lean product system. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1988, 30, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, H.; MacDuffie, J.P. Industrial Relations and 'Humanware; Working Paper; Sloan School of Management: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimori, Y.; Kusunoki, M.; Cho, F.; Uchikawa, S. Toyota production organization and Kanban organisation Materialization of just-in-time and respect-for-homo organisation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1977, 15, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T.I. Toyota Seisan Hoshiki: Datsu-Kibo no Keiei o Mezashite; DiamondYsha: Tokyo, Nippon, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, T. How the Toyota Product System was Created. Jpn. Econ. Stud. 1982, ten, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Thou.; Hoshino, Y. The Anatomy of Japanase Business; M.Eastward. Sharpe Inc.: Armonk, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Shingo, S.; Dillon, A.P. A Report of the Toyota Production System: From an Industrial Engineering Viewpoint (Produce What Is Needed, When It'southward Needed); CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, Usa, 1898. [Google Scholar]

- Monden, Y. Toyota Product System: Applied Approach to Product Management; Industrial Engineering and Management Press, Institute of Industrial Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Schonberger, R.J. Japanese Manufacturing Techniques: Nine Hidden Lessons in Simplicity; The Costless Press: New York, NY, Us, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.W. Zero Inventory; Dow Jones-Irwin Professional Pub: Homewood, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, R.W.; Hall, J. Attaining Manufacturing Excellence: Just-in-Time, Full Quality, Full People Involvement; Dow Jones-Irwin Professional Pub: Homewood, IL, Us, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano, M.A. The Japanese Machine Industry: Technology and Management at Nissan and Toyota. Council on East Asian Studies; Harvard Academy Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shingō, S. A Revolution in Manufacturing: The SMED Arrangement; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Management Association. Kanban But-in Time at Toyota: Direction Begins at the Workplace; Productivity Printing: New York, NY, Usa, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, M. Kaizen (Ky'zen): The Key to Nippon's Competitive Success; Random Housre Business Sectionalisation: New York, NY, United states of america, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, S. Introduction to TPM: Total Productive Maintenance; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, T. Toyota Production Organisation: Beyond Big-Calibration Production; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Thou.; Haslam, C.; Williams, J.; Cultler, T.; Adcroft, A.; Johal, Southward. Against lean production. Econ. Soc. 1992, 21, 321–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, C. Lean Production—The End of History? Work. Employ. Soc. 1993, 7, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, One thousand. The limits of "Lean". Sloan Manag. Rev. 1994, 35, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Delbridge, R.; Oliver, Northward. Narrowing the gap? Stock turns in the Japanese and Western car industries. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1991, 29, 2083–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. From lean production to the lean enterprise. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 1996, 24, iv. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bicheno, J. The Lean Toolbox; PICSIE Books: Buckingham, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marodin, G.A.; Saurin, T. Implementing lean production systems: Inquiry areas and opportunities for future studies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 6663–6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, H.; Wenxing, L. The Analysis of Industry four.0 and Lean Production. In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium-Management, Innovation and Evolution, Guangzhou, China, i Dec 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rossini, K.; Costa, F.; Tortorella, G.; Portioli-Staudacher, A. The interrelation betwixt Industry iv.0 and lean production: An empirical study on European manufacturers. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 3963–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciano, M.P.; Dallasega, P.; Orzes, G.; Rossi, T. One-to-1 relationships between Industry iv.0 technologies and Lean Production techniques: A multiple example study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 59, 1386–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C. Lean Manufacturing Organization, 21st Century. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference Proceedings-American Product and Inventory Control Social club, 1 Nov 1993; Available online: https://www.amazon.com/International-Conference-Proceedings-INTERNATIONAL-PROCEEDINGS/dp/1558221042 (accessed on 28 Oct 2021).

- Shah, R.; Ward, P.T. Lean manufacturing: Context, practice bundles, and performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2002, 21, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasti, Northward.5.Yard.; Kodali, R. A literature review of empirical research methodology in lean manufacturing. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 1080–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.; Elangeswaran, C.; Wulfsberg, J. Industry 4.0 implies lean manufacturing: Inquiry activities in industry 4.0 function as enablers for lean manufacturing. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2016, 9, 811–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valamede, L.S.; Akkari, A.C.S. Lean Manufacturing and Industry 4.0: A Holistic Integration Perspective in the Industrial Context. 2020, pp. 63–68. Bachelor online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstruse/document/9080393 (accessed on 28 Oct 2021).

- Fynes, B.; Ennis, South. From lean production to lean logistics: The case of microsoft Ireland. Eur. Manag. J. 1994, 12, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, R. Squaring lean supply with supply chain management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1996, 16, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huallacháin, B.; Wasserman, D. Vertical Integration in a Lean Supply Chain: Brazilian Automobile Component Parts*. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 75, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.; De Castro, R.; Simons, D.; Gimenez, G. Development of lean supply chains: A case report of the Catalan pork sector. Supply Concatenation Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Buendia, Due north.; Moyano-Fuentes, J.; Maqueira-Marín, J.Yard.; Cobo, Chiliad.J. 22 Years of Lean Supply Chain Management: A science mapping-based bibliometric assay. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 59, 1901–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, Chiliad.50.; Miorando, R.F.; Fries, C.Due east.; Vergara, A.M.C. On the relationship betwixt Lean Supply Chain Management and performance improvement by adopting Industry iv.0 technologies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Paris, France, 26–27 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tortorella, G. Erratum. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Merino, M.; Maqueira-Marín, J.M.; Moyano-Fuentes, J.; Martínez-Jurado, P.J. Information and digital technologies of Manufacture 4.0 and Lean supply concatenation management: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 5034–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.T.; Hines, P.; Rich, N. Lean logistics. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 1997, 27, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, O.; Zsifkovits, H.Due east. Business procedure re-applied science as an enabling cistron for lean management. In Proceedings of the IFIP TC8 Open up Conference on Business Process Re-engineering: Information Systems Opportunities and Challenges, Queensland Golden Coast, Commonwealth of australia, 8–eleven May 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Jurado, P.J.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Lean Management, Supply Concatenation Management and Sustainability: A Literature Review. J. Make clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.; Jirsak, P.; Lorenc, Thou. Industry 4.0. the Cease Lean Management? In The tenth International Days of Statistics and Economics; Melandrium: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016; pp. 1189–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Jasti, N.V.K.; Kota, S.; Kale, S.R. Evolution of a framework for lean enterprise. Meas. Passenger vehicle. Excel. 2020, 24, 431–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, U.; Wullbrandt, J.; Fochler, S. Center of Excellence for Lean Enterprise four.0. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 31, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, L. Lean production in lean structure. In Proceedings of the National Construction and Management Conference, Sydney, Australia, 17–xviii February 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, H.R.; Horman, Thousand.J.; De Souza, U.E.Fifty.; Završki, I. Reducing Variability to Ameliorate Performance equally a Lean Construction Principle. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2002, 128, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, O.; Solomon, J.; Genaidy, A.; Minkarah, I. Lean Construction: From Theory to Implementation. J. Manag. Eng. 2006, 22, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, L.; Ferrantelli, A.; Niiranen, J.; Pikas, E.; Dave, B. Epistemological Explanation of Lean Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04018131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekan, A.; Clinton, A.; Fayomi, O.S.I.; James, O. Lean Thinking and Industrial four.0 Approach to Achieving Structure 4.0 for Industrialization and Technological Development. Buildings 2020, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, A.P.; Da Costa, Due south.E.One thousand.; De Lima, E.P. Criticality assessment of the barriers to Lean Construction. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2020, 70, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. Lean and Greenish: The Motion to Environmentally Conscious Manufacturing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 39, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.A.; Lenox, M.J. Lean and green? An empirical examination of the relationship between lean production and environmental operation. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2009, 10, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainuma, Y.; Tawara, N. A multiple attribute utility theory approach to lean and greenish supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 101, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Reyes, J.A. Lean and green—A systematic review of the state-of-the-art literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, xviii–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, L.K.S.; Santos, L.C.; Gohr, C.F.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Amorim, M.H.D.S. Criteria and practices for lean and green operation assessment: Systematic review and conceptual framework. J. Make clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 746–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, L.One thousand.S.; Santos, L.C.; Gohr, C.F.; Rocha, L.O. An ANP-based approach for lean and green performance assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 143, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, S.R.; Cauchick-Miguel, P.A.; Campos, Fifty.M.South. Product-service systems towards eco-effective product patterns: A Lean-Green design approach from a literature review. Total. Qual. Manag. Coach. Excel. 2019, 32, 1046–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.; Cabrita, Chiliad.D.R.; Cruz-Machado, V. Business Model, Lean and Green Management and Industry four.0: A Conceptual Relationship. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2019, i, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.D.; Teng, Southward.Y.; How, B.S.; Ngan, S.L.; Rahman, A.A.; Tan, C.P.; Ponnambalam, S.; Lam, H.50. Enhancing the adaptability: Lean and light-green strategy towards the Industry Revolution 4.0. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, Northward.F.; Morgan, N.A. The bear upon of lean thinking and the lean enterprise on marketing: Threat or synergy? J. Marking. Manag. 1997, 13, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, 5.L.; Alves, A.; Leão, C.P. Industry 4.0 triggered by Lean Thinking: Insights from a systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 59, 1496–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, C.; Ahlstrom, P. The difficult path to lean product evolution. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1996, 13, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, H.C.M.; Farris, J.A. Lean Product Evolution Research: Current State and Time to come Directions. Eng. Manag. J. 2011, 23, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liker, J.K.; Morgan, J.M. The Toyota Way in Services: The Case of Lean Product Development. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2006, 20, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Pezzotta, G.; Rossi, M.; Terzi, Due south.; Cavalieri, Due south. Towards a Lean Product Service Systems (PSS) Pattern: State of the Fine art, Opportunities and Challenges. Procedia CIRP 2015, xxx, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Rossi, M.; Pezzotta, Thousand.; Pacheco, D.; Terzi, Due south. Defining lean product service systems features and research trends through a systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Lifecycle Manag. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.East.; Youngdahl, W.Eastward. "Lean" service: In defense of a product-line approach. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, C.K. The lean service machine. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Barraza, M.F.; Smith, T.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.Thousand. Lean Service: A literature analysis and classification. Full. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2012, 23, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprigg, C.A.; Jackson, P.R. Telephone call centers equally lean service environments: Job-related strain and the mediating role of work design. J. Occup. Heal. Psychol. 2006, 11, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piercy, N.; Rich, N. High quality and low cost: The lean service centre. Eur. J. Marking. 2009, 43, 1477–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGanga, L.R. Lean service operations: Reflections and new directions for capacity expansion in outpatient clinics. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, M. Lean services: A systematic review. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 1025–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, J.H. "Lean Sigma" Synergy. Ind. Week 2000, 249, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Furterer, Due south.; Elshennawy, A.G. Implementation of TQM and lean Half dozen Sigma tools in local authorities: A framework and a instance study. Total. Qual. Manag. Motorcoach. Excel. 2005, xvi, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheat, B.; Mills, C.; Carnell, M. Leaning into 6 Sigma: A Parable of the Journey to Six Sigma and a Lean Enterprise; McGraw Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; Antony, J.; Singh, R.; Tiwari, Grand.Grand.; Perry, D. Implementing the Lean Sigma framework in an Indian SME: A case study. Prod. Programme. Control. 2006, 17, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albliwi, Due south.A.; Antony, J.; Lim, Southward.A.H. A systematic review of Lean Six Sigma for the manufacturing industry. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2015, 21, 665–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.C.1000.; Broday, E.E. Comparative analysis between the industrial and service sectors: A literature review of the improvements obtained through the application of lean six sigma. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2018, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, One thousand. Design of cyber physical organisation architecture for industry 4.0 through lean 6 sigma: Conceptual foundations and research bug. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2020, 8, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, A.; Kumar, M. Lean Six Sigma and Industry 4.0 integration for Operational Excellence: Evidence from Italian manufacturing companies. Prod. Plan. Control. 2020, 32, 1084–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Printing Development Team. The Lean Office, Nerveless Practices & Cases; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Locher, D. Lean Function and Service Simplified: The Definitive How-To Guide; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Herkommer, J.; Herkommer, O. Lean Office-System. Z. Wirtsch. Fabr. 2006, 101, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, M.; Knight, C.; Postmes, T.; Haslam, S.A. The relative benefits of green versus lean office space: Three field experiments. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2014, xx, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.D.C.; Freitas, Thou.D.C.D. Information management in lean function deployment contexts. Int. J. Lean 6 Sigma 2020, 11, 1161–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.T.; DE Oliveira, K.A.; Futami, A.H. A Systematic Literature Review on Lean Office. Ind. Eng. Manag. Syst. 2019, eighteen, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portioli-Staudacher, A. Lean Healthcare. An Feel in Italia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graban, M. Lean Hospitals: Improving Quality, Patient Safe, and Employee Date; CCR Press, Taylor & Francis Grouping: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgaard, J.J.; Pettersen, J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.G. Quality and lean health care: A arrangement for assessing and improving the health of healthcare organisations. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2011, 22, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.B.M.; Filho, G.1000. Lean healthcare: Review, classification and analysis of literature. Prod. Plan. Control. 2016, 27, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.D.S.Yard.D.; Reis, A.; De Souza, C.G.; Dos Santos, I.Fifty.; Ferreira, 50.A.F. The first evidence about conceptual vs analytical lean healthcare research studies. J. Heal. Organ. Manag. 2020, 34, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, S. Why the lean beginning-up changes everything. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ries, E. The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses; Crown Business organisation: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen, D.L.; Brem, A. How exercise entrepreneurs think they create value? A scientific reflection of Eric Ries' Lean Startup arroyo. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 13, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, R.F.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Danilevicz, A.D.Grand.F.; Ghezzi, A. Lean Startup: A comprehensive historical review. Manag. Decis. 2018, 59, 1765–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.Due south.; Ghezzi, A.; de Aguiar, R.B.; Cortimiglia, One thousand.N.; Caten, C.S.T. Lean Startup, Agile Methodologies and Customer Development for business organization model innovation. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 26, 595–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternich, J.; Müller, M.; Meudt, T.; Schaede, C. Lean 4.0—Zwischen Widerspruch und Vision. ZWF 2017, 112, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, A.; Weigelt, M.; Kühl, A.; Grimm, S.; Erll, A.; Potzel, M.; Franke, J. Lean four.0—A conceptual conjunction of lean management and Industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valamede, L.S.; Akkari, A.C.S. Lean iv.0: A New Holistic Approach for the Integration of Lean Manufacturing Tools and Digital Technologies. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2020, 5, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perico, P.; Mattioli, J. Empowering Process and Control in Lean 4.0 with Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Industries (AI4I), Irvine, CA, USA, 21–23 September 2020; pp. half dozen–nine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmont, K.; Gladysz, B.; Corti, D.; Castaño, F.; Mohammed, W.M.; Lastra, J.L.M. Towards "Lean Industry four.0"—Current trends and time to come perspectives. Denoting Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1781995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.A.; Herrmann, C.; Thiede, S. Manufacture 4.0 Impacts on Lean Product Systems. Procedia CIRP 2017, 63, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buer, South.-V.; Strandhagen, J.O.; Chan, F.T.S. The link betwixt Industry iv.0 and lean manufacturing: Mapping current research and establishing a enquiry agenda. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2924–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.; Cruz-Machado, V. An investigation of lean and green supply chain in the Industry iv.0. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Industrial Technology and Operations Management (IEOM), Rabat, Morocco, xi–13 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ilangakoon, T.; Weerabahu, Due south.; Wickramarachchi, R. Combining Industry four.0 with Lean Healthcare to Optimize Operational Operation of Sri Lankan Healthcare Industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Production and Operations Management Guild (POMS), Peradeniya, Sri Lanka, fourteen–16 December 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, Chiliad. Manufacture four.0 and lean direction: A proposed integration model and research propositions. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2017, 6, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Shankar, R.; Singh, Southward.P. Impact of Industry4.0/ICTs, Lean Six Sigma and quality management systems on organisational performance. TQM J. 2020, 32, 815–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure one. Web of Science search string.

Effigy 1. Web of Science search string.

Figure 2. Scopus search string.

Effigy 2. Scopus search string.

Figure three. SLR procedure overview.

Effigy iii. SLR process overview.

Figure 4. Evolution of papers per year that include "lean" in the championship over the report menses (1988–2020).

Figure 4. Evolution of papers per year that include "lean" in the title over the study period (1988–2020).

Figure 5. Historical evolution of the main lean categories and their foundational works.

Figure 5. Historical development of the master lean categories and their foundational works.

Figure 6. Lean production vs. lean manufacturing evolution.

Figure six. Lean production vs. lean manufacturing evolution.

Effigy 7. Lean logistics and lean supply chain evolution.

Figure seven. Lean logistics and lean supply chain development.

Figure 8. Lean direction evolution.

Figure 8. Lean management evolution.

Figure 9. Lean enterprise evolution.

Figure nine. Lean enterprise evolution.

Figure ten. Lean construction evolution.

Figure 10. Lean structure evolution.

Figure 11. Lean and green development.

Figure 11. Lean and green evolution.

Figure 12. Lean thinking evolution.

Figure 12. Lean thinking evolution.

Figure 13. Lean product evolution.

Figure xiii. Lean product development.

Figure 14. Lean services evolution.

Figure 14. Lean services evolution.

Figure 15. Lean six sigma evolution.

Figure 15. Lean six sigma evolution.

Effigy 16. Lean office evolution.

Figure 16. Lean office development.

Figure 17. Lean healthcare/hospital evolution.

Effigy 17. Lean healthcare/hospital evolution.

Effigy xviii. Lean startup evolution.

Figure 18. Lean startup evolution.

Effigy 19. Papers almost relationships between lean and Industry four.0.

Effigy xix. Papers about relationships between lean and Manufacture 4.0.

Figure twenty. Papers linking lean and Manufacture 4.0 past corresponding writer's country (2015–2020).

Effigy 20. Papers linking lean and Industry four.0 by corresponding author's state (2015–2020).

| Publisher'south Notation: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access commodity distributed under the terms and atmospheric condition of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC By) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/).

DOWNLOAD HERE

Posted by: underwoodknoid1996.blogspot.com

Post a Comment for "Design And Analysis Of Lean Production Systems .Pdf Download UPDATED"